Sulla recente edizione Le Chevalier aux deux épées. Roman en vers du XIIIe siècle, édité, présenté et traduit par Gilles Roussineau, Genève, Droz, 2022.

On the new edition Le Chevalier aux deux épées. Roman en vers du XIIIe siècle, édité, présenté et traduit par Gilles Roussineau, Genève, Droz, 2022.

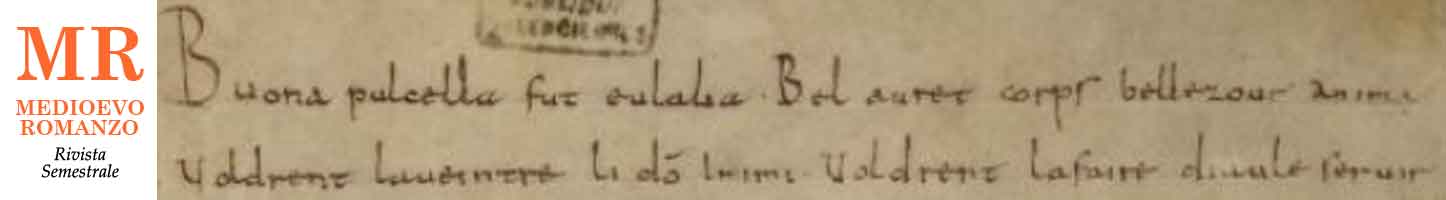

This paper adopts a filologia d’autore approach to the composition of Gianfranco Contini’s 1965 essay Un’interpretazione di Dante, outlining the essay’s multiple redactions between the winter of 1964 and the autumn of 1965, when it was published in «Paragone». It shows that Contini’s «famoso saggio» (Pasolini) developed from public-facing work – both Contini’s work curating the 1965 Mostra di codici danteschi in Florence, as well as a number of translations produced for public talks Contini gave in Canada, Malta, Austria, Russia and the UK. It then offers a close analysis of the production of Contini’s signature «untranslatable» (Calvino) style in the final published work, based on autograph material held in the Archivio Gianfranco Contini.

Il riesame del canzoniere trobadorico T (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, fr. 15211), condotto con la lampada di Wood, ha consentito di rilevare le tracce di una strofe di Per cinq en podetz demandar (BdT 96,9) del poeta Blacasset. La porzione di testo, erasa dal copista, si posiziona in corrispondenza di una cobla di A Lunel lutz una luna luzens (BdT 225,1) di Guilhem de Montanhagol (c. 280r). Questo episodio di riscrittura pone nuovi interrogativi su due aspetti importanti per lo studio del canzoniere T: da una parte, la logica alla base dell’ordinamento e del contenuto dell’antologia trobadorica; dall’altra, il “comportamento” del copista nei confronti del materiale poetico a sua disposizione. In base a questi dati, l’articolo fornisce un’analisi linguistica ed ecdotica del frammento della cobla di Blacasset, anche alla luce della sezione del canzoniere in cui essa era originariamente trascritta.

The re-examination of the troubadour songbook T (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, fr. 15211), conducted with the Wood’s lamp, has allowed for the detection of traces of a stanza from Per cinq en podetz demandar (BdT 96,9) by the poet Blacasset. The strophe, erased by the scribe, is positioned in correspondence with a cobla from A Lunel lutz una luna luzens (BdT 225,1) by Guilhem de Montanhagol (c. 280r). This episode of rewriting raises new questions about two important aspects for the study of the songbook T: on one hand, the logic behind the organization and content of the troubadour anthology; on the other hand, the scribe's "behavior" towards the poetic material at his disposal. Based on this data, the article provides a linguistic and philological analysis of the fragment of Blacasset’s stanza, also in light of the section of the songbook in which it was originally transcribed.

Il contributo, che si inserisce all’interno della prospettiva di studi che ha riletto – alla luce dei presupposti teorici forniti da G.G. Corbett – i sistemi di genere delle varietà romanze medievali e moderne, propone un’analisi quantitativa e qualitativa del cosiddetto terzo genere nel napoletano antico. I testi due-trecenteschi, infatti, rappresentano un punto di osservazione privilegiato della fase di transizione da un genere con accordo plurale dedicato in -a (es. la sua fortissima brazia) a un genere con accordo plurale in -e, identico a quello femminile (es. le smagrate corpora).

The paper, which follows the latest researches that have reinterpreted – under the theoretical premises provided by G.G. Corbett – Romance varieties gender systems, provides a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the so-called third gender in Old Neapolitan. The earliest texts represent a privileged observation point for the transitional phase from a gender with a dedicated plural agreement -a (e.g. la sua fortissima brazia) to a gender with a feminine plural agreement (e.g. le smagrate corpora).

Este artículo ofrece la edición completa y análisis pormenorizado de dos vocabularios hebreo-castellanos, incluidos en el Ms. 5456 de la Biblioteca Nacional de España. El primero presenta, en una cuadrícula que se lee de derecha a izquierda, los lemas hebreos con traducción castellana supralineal. El segundo, dispuesto de manera más irregular, primero en columnas ordenadas de derecha a izquierda y después a línea tirada, tiene la particularidad de transcribir la mayor parte de los lemas hebreos en caracteres latinos. Aunque la existencia de estos vocabularios se conocía, su contenido no se había editado y estudiado hasta la fecha. Los vocabularios están copiados en un cuaderno que se inserta en un códice no unitario de contenido bíblico, en algunas de cuyas secciones aparecen también anotaciones marginales en castellano. Ambos dan testimonio de los métodos de aprendizaje de la Biblia hebrea en época tardo-medieval entre alumnos no judíos.

This article offers the complete edition and detailed analysis of two Hebrew-Castilian vocabularies, included in Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ms. 5456. The first one presents, in a grid that reads from right to left, the Hebrew lemmas with supralinear Castilian translation. In the second one, arranged in a more irregular way, first in columns ordered from right to left and then in a single column, most of the Hebrew lemmas appear transcribed in Latin characters. Although the existence of these vocabularies was known, their contents had not been edited and studied to date. The vocabularies are copied in a notebook that is inserted in a non-unitary codex of biblical content, in some of whose sections there are also marginal annotations in Spanish. Both testify to the methods of learning the Hebrew Bible in late medieval times among non-Jewish students.

Nel racconto Striges del Sendebar, narrato dalla matrigna, è rintracciabile una fitta serie di corrispondenze tra la misteriosa vicenda esperita dal suo protagonista e gli eventi nei quali è coinvolto l’Infante nella storia-cornice, corrispondenze che inducono il destinatario ultimo, il lettore, e che avrebbero dovuto indurre il destinatario primo, Alcos, a riconoscere nella malvagia «diabla» del cuento la favorita del re e ad associare le trame tessute dall’una con le manovre poste in essere dall’altra. Come a dire che la matrigna, anziché parlare a proprio vantaggio, sembrerebbe addurre paradossalmente argomenti a sostegno del figliastro, ammettendo così la propria colpevolezza. La deficienza espositiva e persuasiva della matrigna è funzionale alle finalità sapienziali-misogine del testo: l’avversione del Sendebar per la donna invade anche lo spazio dei racconti esposti dalla moglie di Alcos per controbattere alla tesi sulla malizia femminile sostenuta con i loro racconti dai sette consiglieri del re, minandone l’esemplarità. Gli enxenplos postile in bocca veicolano una “seconda intenzione”, quella dell’autore del Libro, che non collima con l’intenzione “prima” e con gli interessi di colei che li narra. Una “visione del mondo” che si impone attribuendo alla parola femminile i tratti negativi dell’oscurità sinistra, dell’incongruenza, dell’inadeguatezza, dell’irrazionalità istintiva, a sottolinearne assieme l’inferiorità ma anche la temibile pericolosità. A fare da discrimine, nel Sendebar come in opere consimili, è l’uso, buono o cattivo, che si fa del saber. La «diabla» di Striges è causa della propria perdizione per l’incauto suggerimento che, al fine di irretirlo (dunque un sapere male impiegato), fornisce al principe; allo stesso modo, nella storia portante, la moglie infedele del re è causa della propria condanna a essere bruciata «en una caldera en seco» per i suoi controproducenti interventi verbali. Come il principe del racconto, l’Infante fa invece tesoro della conoscenza ‒ acquisita nel corso dell’apprendistato (che include anche la prova del silenzio) al quale è stato sottoposto ‒ della vera natura della matrigna, e venuto meno l’obbligo del silenzio se ne avvale (si tratta, dunque, di un saber bueno) per ristabilire la verità e ripristinare la giustizia.

In Sendebar’s tale Striges, narrated by the stepmother, a dense series of correspondences can be found between the mysterious events experienced by its protagonist and the events in which the Infante is involved in the frame-story, correspondences that induce the final addressee, the reader, and that should have induced the first addressee, Alcos, to recognise the king's favourite in the evil «diabla» of the cuento and to associate the plots woven by one with the manoeuvres carried out by the other. As if to say that the stepmother, instead of speaking for her own benefit, would paradoxically seem to be putting forward arguments in support of her stepson, thus admitting her own guilt. The stepmother's expositional and persuasive deficiency is functional to the sapiential-misogynistic aims of the text: Sendebar’s aversion to women also invades the space of the tales expounded by Alcos’ wife to counter the thesis on female malice sustained with their tales by the king’s seven councillors, undermining its exemplarity. The enxenplos placed in her mouth convey a “second intention”, that of the author of the Book, which does not collide with the “first intention” and the interests of she who narrates them. A “worldview” that imposes itself by attributing to the female word the negative traits of sinister obscurity, incongruity, inadequacy, and instinctive irrationality, underlining not only its inferiority but also its fearsome danger. The discriminating factor, in Sendebar as in similar works, is the use, good or bad, that is made of the saber. The «diabla» of Striges is the cause of her own perdition because of the incautious suggestion she gives to the prince in order to ensnare him (thus an ill-used knowledge); similarly, in the carrier story, the unfaithful wife of the king is the cause of her own condemnation to be burnt «en una caldera en seco» for her counterproductive verbal interventions. Like the prince in the story, the Infante instead treasures the knowledge ‒ acquired in the course of the apprenticeship (which also includes the test of silence) to which he has been subjected ‒ of the stepmother's true nature, and once the obligation of silence has ceased, he makes use of it (it is, therefore, a saber bueno) to re-establish the truth and restore justice.

Come Dante e Petrarca, anche Boccaccio connette una costante numerologica alla sua amata, Fiammetta: il numero 5, in passato associato al numero di lettere del nome reale della donna, Maria D’Aquino. Fra i suoi significati simbolici, molti dei quali rintracciabili nell’opera di Boccaccio, il numero 5 ne ha uno sinora trascurato, quello mariano, di cui l’autore si serve per ritrarre Fiammetta come una figura Mariae in maniera più marcata rispetto alle altre due Corone. L’articolo ripercorre le possibili fonti numerologiche di Boccaccio, mostrando quanto l’accezione mariana del numero 5 fosse in realtà vulgata nel Basso Medioevo e tentando un’interpretazione della sua attribuzione a Fiammetta/Maria.

As though Dante and Petrarch do, Boccaccio links a constant to his beloved, Fiammetta: the number 5, which has been already connected to the letters of the woman’s real name, Maria D’Aquino. Among its symbolic meanings (much of them could be traceable in Boccaccio’s work), number 5 has a sense concerning the Virgin Mary and until now disregarded, that the author makes use of to depict Fiammetta as a figura Mariae in a much pronounced way than the other two Crowns. The paper retraces Boccaccio’s possible sources to show how much the religious sense of number 5 was actually known in the Late Middle Ages and to attempt an interpretation of its connection to Fiammetta/Maria.

Cette étude entend investiguer les dispositifs structuraux et intellectuels mis au service de la réécriture de la Fleur des histoires de Jean Mansel (moitié du xve siècle). Conservée dans au moins deux rédactions, cette chronique universelle subit une transformation qui permet d’analyser le travail de l’historiographe face au texte. Dans cet article, l’attention est portée sur les épisodes qui précèdent les guerres de Troie, en particulier sur la section consacrée à la Grèce des origines qui, constituée par une séquence de mythes indépendants, se prête à l’étude de la reconception architecturale de l’œuvre. Par la comparaison systématique entre les deux versions, l’article fournit une perspective sur les moyens formels employés et sur les buts sémantiques visés au sein de l’opération rédactionnelle de Jean Mansel. De nouvelles hypothèses émergent sur les raisons intellectuelles qui ont motivé la réécriture de l’œuvre : de l’acquisition d’un savoir spécialisé sur la mythologie grecque, au jaillissement d’un culte littéraire savant pour certains héros de l’Antiquité, ou encore l’élaboration – basée sur un dessein de restructuration inachevée – d’une chronique aux unités thématiques plus homogènes.

The aim of this study is to investigate the structural and intellectual mechanisms used by Jean Mansel to rewrite the Fleur des histoires (mid-15th century). Preserved in at least two versions, this universal chronicle underwent a transformation that invites to analyse the historiographer at work while rewriting his text. The article focuses on the episodes preceding the Trojan Wars and, more specifically, on the section of the chronicle dedicated to a sequence of ancient Greek myths that undergoes a structural reshaping. By systematically comparing the two versions, this contribution provides a new perspective on the use of formal resources and on the pursuit of new semantic aims within Jean Mansel’s editorial work. New hypotheses emerge about the intellectual reasons that motivated the rewriting of the chronicle: the acquisition of specialised knowledge about Greek mythology, the emergence of an erudite literary cult of certain Greek heroes, as well as the elaboration – left unfinished by Mansel – of a chronicle organised in homogeneous thematic units.

Les armoriaux arthuriens, réunissant au XVe siècle les armoiries des chevaliers de la Table Ronde, présentent les grands noms de la littérature arthurienne mais recèlent également nombre de chevaliers peu ou prou connus des grands cycles en prose arthuriens, qui se voient dotés d’armoiries et parfois d’une petite notice biographique. Cet article se propose de partir à la recherche de quatre chevaliers de la génération dite «des pères», celle de Guiron le Courtois, pour découvrir de quels textes ces chevaliers ont été tirés et ce que leur origine textuelle signifie, tant pour la réception de la littérature arthurienne à la fin du Moyen Âge que pour les techniques d’innovation à l’œuvre dans la conception des armoriaux des chevaliers de la Table Ronde. Une édition des quatre courtes biographies des chevaliers à l’enquête complète cette étude.

The Arthurian armorials, which in the 15th century bundle the coats of arms of the knights of the Round Table, featured the great names of Arthurian literature, as well as several little-known knights of the great Arthurian prose cycles, the latter of which also were given coats of arms and sometimes a short biographical note. This paper sets out to search for four knights of the generation ‘of the fathers’, thus the one of Guiron le Courtois. It aims to discover from which texts these knights were drawn, and what their textual origin implies, both for the reception of Arthurian literature at the end of the Middle Ages and for the innovative techniques at work in the conception of the armorial bearings of the Knights of the Round Table. An edition of the four short biographies of the considered knights completes this study.