NICOLÒ PASERO, Dante in Cavalcanti. Ancora sui rapporti fa ‘Vita Nuova’ e ‘Donna me prega’ [388-414]

Lo studio riprende la tesi sostenuta da Enrico Malato e Giuliano Tanturli per cui la grande caanzone di Guido Cavalcanti costituirebbe una confutazione delle critiche contenute implicitamente nella Vita Nova contro colui che Dante aveva precedentemente riconosciuto come il suo «primo amico».

The article takes up the thesis put forward by Enrico Malato and Giuliano Tanturli that Guido Cavalcanti's great canzone constitutes a refutation of the criticism implicitly contained in the Vita Nova against the poet whom Dante had previously acknowledged as his 'first friend'.

L’articolo dà conto della scoperta di tre poesie italiane ai ff. 117v-118r di un codice che contiene principalmente il Foucon de Candie. Sotto uno strato linguistico settentrionale imputabile al copista, la lingua delle poesie è quella di un autore bene al corrente dei modi espressivi della poesia toscana della seconda metà del XIII s.

The article gives an account of the discovery of three Italian poems on ff. 117v-118r of a codex containing the Foucon de Candie. Beneath a northern linguistic layer attributable to the copyist, the language of the poems is that of an author well acquainted with the expressive modes of Tuscan poetry in the second half of the 13th century.

L’articolo fornisce un esame dettagliato dei rapporti di derivazione tra le due poesie di Folquet de Marselha e di Rinaldo d'Aquino già peraltro scoperti da Francesco Torraca. La fonte del testo italiano è vicina al testo del canzoniere occitanico T, come del resto già visto da Roberto Antonelli.

The article provides a detailed examination of the derivation relations (already discovered by Francesco Torraca) between the two poems by Folquet de Marselha and Rinaldo d'Aquino. As already seen by Roberto Antonelli, the source of the Italian text is close to the text of the Occitan songbook T.

Cette étude entend réhabiliter la tradition française du Livre don Devisement du monde qui ne peut pas être réduite à un remaniement par rapport à la branche francovénitienne représentée par le ms. BNF 1116, comme le voulait L. F. Benedetto. Un des principaux arguments de ce dernier est le fruit d'une faute de lecture, puisque la rubrique du ms. Al donne (comme A3): «ceste livre [...] le quel je Grigoire, contrescris du livre de messire Marc Pol» et non contrefais. Il est ainsi plus prudent d'affirmer que Grégoire est le copiste auquel remonte cette famille de manuscrits plutôt que le responsable du ‘remaniement’.

This study aims to rehabilitate the French tradition of the Livre don Devisement du monde, which cannot be reduced to a reworking of the Franco-Venetian branch represented by ms. BNF 1116, as L. F. Benedetto intended. One of his main arguments is in fact the result of a misreading, since the heading of ms. Al gives (as A3): «ceste livre [...] le quel je Grigoire, contrescris du livre de messire Marc Pol» and not contrefais. It follows that it is safer to assert that Grégoire is the copyist to whom this family of manuscripts can be traced rather than the person responsible for the 'reworking'.

Il «merdier do cocodrile» del v. 48 1 e «cocodrili de stercore» del v. 486 corrispondono a un cosmetico ottenuto a partire da escrementi di coccodrillo, di cui è fatta menzione da Plinio il vecchio e nell'epodo n. 12 di Orazio. In particolare il commento di Pomponio Porfirione al poeta latino coinciderebbe con la fonte utilizzata da Gautier.

The «merdier do cocodrile» of l. 481 and the «cocodrili de stercore» of l. 486 correspond to a cosmetic obtained from crocodile excrement, mentioned by Pliny the Elder and in Horace's epode no. 12. In particular, Pomponius Porphyry's commentary on the Latin poet would coincide with the source used by Gautier.

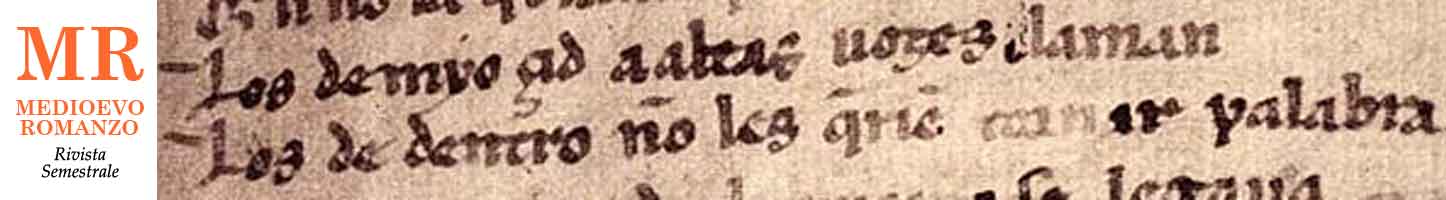

Analisi dei relitti di una tradizione epica precedente l'epopea del Cid. Un frammento di cantarcillo cantato dopo la battaglia di Calatañazor (1002), conservato nel Chronicon mundi di Lucas de Tuy (1236), e un cantarcillo su Corraquín Sancho che si riferisce ad avvenimenti del 1158 nella Chronica de la población de Ávila (ca. 1255), rappresenterebbero una tradizione epica tutta iberica che avrebbe fatto ricorso a forme liriche. Per contro, la celebre Nota emilianense (XI sec.), per quanto redatta in latino, lascia supporre l’esistenza di un originale spagnolo (i nomi di Rodlane e Bertlane presentano l’antica -e di appoggio), testimonianza della parallela esistenza di una forma epica di ispirazione francese.

This study provides an analysis of the relics of an epic tradition preceding the epic of the Cid. A fragment of a cantarcillo sung after the battle of Calatañazor (1002), preserved in the Chronicon mundi by Lucas de Tuy (1236), and a cantarcillo about Corraquín Sancho that refers to events of 1158 in the Chronica de la población de Ávila (ca. 1255), would represent an all-Iberian epic tradition that would have made use of lyrical forms. On the other hand, the famous Nota emilianense (11th cent.), although written in Latin, suggests the existence of a Spanish original (the names Rodlane and Bertlane have the ancient vocal epenthesis -e), evidence of the parallel existence of a French-inspired epic form.