L'autore conferma, attenendosi alla tradizione manoscritta, le ipotesi finora proposte circa l'attribuzione a Gui de Cavaillon delle poesie di Esperdut BdT 142.1-3 e di Guionet BdT 238.1, la, 2, 2a, 3. Nel canzoniere D, la tenço d'Esperdut con Pons de Montlaur BdT 142, 3 precede il sirventes di Gui de Cavaillon BdT 192.4; il fatto che nel manoscritto le due poesie siano distinte dalle cifre j e ij proverebbe che appartengono allo stesso autore. L’esame delle sezioni di tenzoni dei canzonieri ADN GQ CE mostra inoltre come in gruppi di manoscritti di tradizione diversa, le poesie di Esperdut, Guionet e Gui de Cavaillon si seguono in serie relativamente omogenee. Si nota infine come nella tenzone con Ricau de Tarascon Cabrit al meu vejaire 192.la, l'appellativo di Cabrit con cui Ricau apostrofa Gui costituisce un senhal reciproco: nella tornada di BdT 192.4, conservata dal solo frammento T°, Gui si rivolge infatti a Ricau con il nome di Cabrit de Tarascón.

By studying the manuscript tradition, the author confirms the hypotheses proposed so far regarding the attribution of the poems of Esperdut BdT 142.1-3 and Guionet BdT 238.1, la, 2, 2a, 3 to Gui de Cavaillon. In the songbook D, Esperdut's tenço with Pons de Montlaur BdT 142, 3 precedes Gui de Cavaillon's sirventes BdT 192.4; the fact that the two poems are distinguished in the MS. by the numbers j and ij would prove that they belong to the same author. Examination of the tensos sections of MSS. ADN GQ CE also shows how in groups of manuscripts of different traditions, the poems of Esperdut, Guionet and Gui de Cavaillon follow each other in relatively homogeneous series. Finally, it can be remarked that in the tenso with Ricau de Tarascon Cabrit al meu vejaire 192.la, the appellation Cabrit with which Ricau adresses Gui constitutes a ‘reciprocal senhal’ as proved by the fact that in the tornada of BdT 192.4, preserved from the T° fragment alone, Gui addresses Ricau as Cabrit de Tarascón.

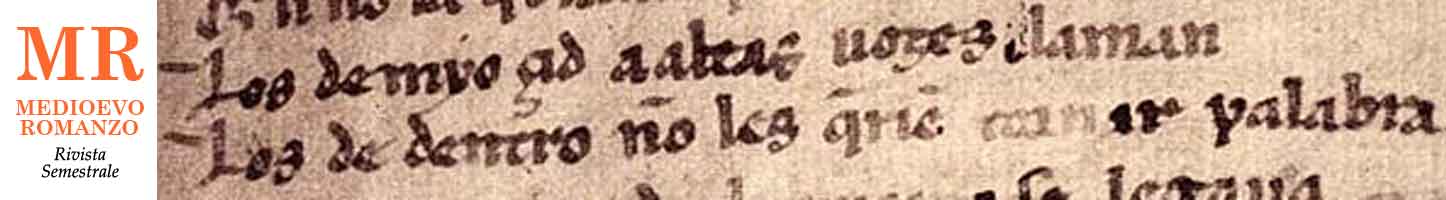

La primera parte del artículo ofrece un análisis de la teoría de los estilos contenida en el prólogo. En la segunda parte, se observa que la transformación del nombre del personaje Eulio de la fuente clásica en pater Queruli procede de una adaptación métrica. Por último, se aborda la cuestión del conocimiento directo del poema de Lucrecio por parte de Vitale de Blois.

The first part of the article offers an analysis of the theory of styles contained in the prologue. In the second part, it is observed that the transformation of the name of the character Eulio from the classical source into pater Queruli stems from a metrical adaptation. Finally, the question of Vitale de Blois' direct knowledge of Lucretius' poem is taken into consideration.

El artículo ofrece unas reflexiones sobre el papel del actor medieval a través del análisis de las leyendas de varios textos (el drama de Peregrinus en las versiones de Rouen y de Fleury-sur-Loire, el Ludus del Anticristo o de Tegernsee, el Ludus de passione Dei de los Carmina Burana, el Ordo ad representandum Herodem de Fleury, el Jeu d'Adam). El actor es un clérigo que actúa como aficionado (diferente en esto del juglar que es un profesional del espectáculo), cuya actividad está sometida al control de las autoridades eclesiásticas.

Reflections on the role of the medieval actor through an analysis of the captions of a number of texts (the drama of Peregrinus in the Rouen and Fleury-sur-Loire versions, the Ludus of the Antichrist or of Tegernsee, the Ludus de passione Dei from the Carmina Burana, the Ordo ad representandum Herodem of Fleury, the Jeu d'Adam). The actor is a cleric who acts as an amateur (different in this from the jester who is a professional) and whose activity is subject to the control of the ecclesiastical authorities.