L’articolo analizza una glossa presente nel manoscritto Par. lat. 9347 (Reims, IX secolo) contenente i Carmina di Venanzio Fortunato. La glossa interpreta il termine grafioli come un piatto culinario fatto di pasta ripiena, cotta nel grasso, anziché nel significato tecnico di “innesto” legato all’arboricoltura. Si esplora l’origine del termine, ipotizzando una derivazione germanica (krâpho/krâfo) e la sua romanizzazione precoce. Si evidenzia una possibile connessione tra il vocabolo grafioli e l’italiano “ravioli”, analizzando l’evoluzione linguistica e culinaria del termine attraverso i secoli. Inoltre, si discute il contesto culturale e linguistico della glossa, suggerendo che il glossatore abbia associato il termine a tradizioni alimentari comunitarie medievali.

The article analyses a gloss in the manuscript Par. lat. 9347 (Reims, 9th century) containing the Carmina of Venantius Fortunatus. The gloss interprets the term grafioli as a culinary dish made of stuffed pasta, cooked in fat, rather than in the technical meaning of “graft” related to arboriculture. The origin of the term is explored, hypothesizing a Germanic derivation (krâpho/krâfo) and its early romanization. A possible connection between the term grafioli and the Italian “ravioli” is highlighted, analyzing the linguistic and culinary evolution of the term through the centuries. Furthermore, the cultural and linguistic context of the gloss is discussed, suggesting that the glossator associated the term with medieval community food traditions.

Nella ‘canzonetta’ S’eo son distretto inamoratamente (V 181) Brunetto Latini inserisce due similitudini animali, ispirandosi direttamente alla canzone Atressi cum l’orifans (421,2) di Rigaut de Barbezill. Il recupero di questa informazione, smarritasi nella bibliografia piú recente su Brunetto, permette anche di precisare la presenza della canzone di Rigaut come fonte diretta di alcuni comportamenti di animali (il cervo e l’orso), descritti nel Tresor. Una verifica su un’altra fonte provenzale già individuata, il trattato sugli Auzels cassadors di Daude de Pradas, modello diretto dei capitoli sul Tresor dedicati ai rapaci, definisce un quadro coerente, associabile con il passaggio di Brunetto nel Sud della Francia e con il suo soggiorno in Montpellier.

In the canzonetta S’eo son distretto inamoratamente (V 181), Brunetto Latini includes two animal similes, directly inspired by the troubadour chanson Atressi cum l’orifans (421,2) by Rigaut de Barbezill. The recovery of this information, which has been lost in more recent scholarship on Brunetto, also allows us to identify Rigaut’s chanson as a direct source for certain animal behaviors (the deer and the bear) described in the Tresor. A cross-check with another already identified Provençal source – the treatise about the Auzels cassadors by Daude de Pradas, a direct model for the chapters on birds of prey in the Tresor – helps to define a coherent framework, which can be associated with Brunetto’s journey through southern France and his stay in Montpellier.

La Biblioteca «Lodovico Jacobilli» della Diocesi di Foligno conserva un manoscritto del Devisement dou monde rimasto finora ignoto agli studi poliani. Il manoscritto, identificato con la segnatura A.II.9, è databile tra la fine del XIV e l’inizio del XV secolo e trasmette il testo nella redazione settentrionale nota come VA. L’articolo propone una ricognizione di questo nuovo testimone: dopo una presentazione delle caratteristiche della famiglia VA, si offre una descrizione codicologica del manoscritto, seguita dalla sua collocazione all’interno dello stemma codicum.

The “Lodovico Jacobilli” Library of the Diocese of Foligno holds a previously unknown manuscript of the Devisement dou monde. Catalogued as A.II.9, the manuscript dates from the late 14th or early 15th century and belongs to the Northern Italian version of the text, known as VA. This paper examines this newly identified witness: after outlining the key features of the VA family, it provides a codicological description of the manuscript and evaluates its place within the stemma codicum.

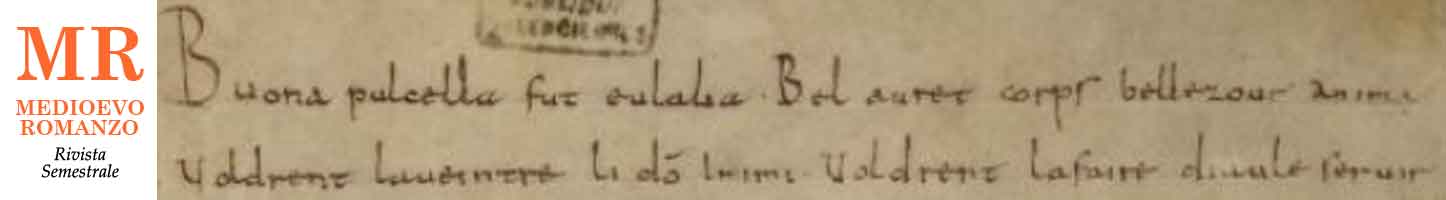

Fattori in gran parte esterni al testo, uniti a spie contenutistiche, formali, stilematiche, mi hanno indotto ad avanzare un’inedita proposta attributiva per il lacerto lirico adespoto e anepigrafo ricopiato in uno spazio bianco, in fondo alla sezione Db del canzoniere provenzale estense riservata a Peire Cardenal, e a supporre che il frammento pervenuto sia l’unico anello superstite d’una probabilmente più estesa catena discorsiva, di un dialogo in versi svoltosi tra Giraut de Salaignac e Uc de Saint Circ.

A combination of factors largely eternal to the text, together with formal, stylistic features and indications relating to its content have prompted me to propose a new attribution for the anonymous and unascribed lyric fragment which was copied into a blank space and the end of the Peire Cardenal section of the Occitan known as D (Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, α R.4.4), and to suggest that these lines represent the only surviving element of a more extensive textual sequence: a poetic dialogue between Giraut de Salignac and Uc de Saint-Circ.

El trabajo presenta un recorrido historiográfico de los tratados y manuales en español que se han ocupado de la gramática del castellano medieval. Frente a las gramáticas históricas de sincronías pretéritas extensamente desarrolladas para el francés o el italiano, para español tradicionalmente se han escrito historias de la lengua de amplia cronología, en las que la historia externa estructura la periodización y la presentación de la historia interna. El recorrido se inicia en los trabajos pioneros de Menéndez Pidal y se comenta la producción de los autores que le siguieron, como Vicente García de Diego, Rafael Lapesa y los discípulos de este, hasta llegar a los manuales colectivos contemporáneos. Finalmente, el artículo reflexiona sobre el futuro de los estudios sobre la variedad medieval, destacando las nuevas herramientas metodológicas y enfoques interdisciplinarios que están permitiendo ofrecer una renovada visión del castellano antiguo.

The paper presents a historiographical overview of the treatises and manuals in Spanish that have addressed the grammar of Medieval Castilian. Unlike the extensively developed historical grammars focused on past synchronies for French or Italian, studies on Spanish have traditionally taken the form of broad chronological histories of the language, in which external history structures the periodization and presentation of internal history. The overview begins with the pioneering work of Menéndez Pidal and discusses the contributions of subsequent authors such as Vicente García de Diego, Rafael Lapesa, and Lapesa’s disciples, leading up to contemporary collective manuals. Finally, the article reflects on the future of studies on the medieval variety, highlighting new methodological tools and interdisciplinary approaches that are enabling a renewed understanding of Old Spanish.

Il saggio esamina le principali implicazioni teoriche ed empiriche di un approccio sincronico allo studio delle lingue del passato, con particolare attenzione al contributo offerto dalla Grammatica dell’italiano antico (GIA) di G. Salvi e L. Renzi alla conoscenza del fiorentino delle origini. Nel corso dell’analisi vengono considerate le critiche piú rilevanti mosse da una parte della comunità scientifica ai presupposti teorici dell’opera. Successivamente, si approfondisce l’esame di un’altra grammatica sincronica dedicata a una varietà italiana antica, la Grammatica del veneto delle origini (GraVO), diretta da Jacopo Garzonio, evidenziando come il modello di analisi elaborato da Salvi e Renzi possa essere proficuamente esteso e adattato ad altri volgari medievali. Infine, si riflette sull’impostazione teorica della Sintassi dell’italiano antico (SIA) a cura di M. Dardano, per valutare se essa possa essere considerata a pieno titolo una grammatica sincronica.

The paper explores the main theoretical and empirical implications of a synchronic approach to the study of historical languages, with particular focus on the contribution of the Grammatica dell’italiano antico (GIA), ed. by G. Salvi and L. Renzi, to the understanding of Old Italian. The analysis addresses the most significant criticisms put forward by some scholars regarding the theoretical premises of the work. Subsequently, the discussion examines another synchronic grammar dedicated to an Old Italian variety, the Grammatica del veneto delle origini (GraVO), by Jacopo Garzonio, highlighting how the analytical model developed by Salvi and Renzi can be effectively extended and adapted to other medieval vernaculars. Finally, the essay reflects on the theoretical framework of the Sintassi dell’italiano antico (SIA), ed. by M. Dardano, to assess whether it can be regarded as a fully-fledged synchronic grammar.

Notre état des lieux repose sur la comparaison d’une quinzaine de grammaires médiévales publiées depuis le début du 20e siècle. Sont d’abord abordées les limites temporelles (ancien/moyen français) et géographiques des grammaires, ainsi que les types de faits linguistiques (morphologie, syntaxe, phonographie, etc.) traités dans ces ouvrages. Les corpus des grammaires sont ensuite décrits du point de vue de la quantité, de la représentativité et de la diversité des sources. Le traitement de la variation (diachronique, diatopique, etc.), particulièrement importante au Moyen Âge, fait l’objet d’une troisième section. La place de la théorie est enfin brièvement évoquée. Cet état des lieux permet d’observer de quelle manière les grammaires ont accompagné et diffusé les avancées de la recherche sur l’histoire du français et le français du Moyen Âge. Dans une section conclusive, quelques pistes d’évolution sont proposées, mettant en avant les perspectives diachronique et variationnelle en plein essor depuis quelques dizaines d’années.

Our overview is based on a comparison of around fifteen grammars of Medieval French published since the early 20th century. We first address the temporal periods (Old French vs. Middle French) and geographical coverage of the grammars, as well as the types of linguistic phenomena they describe (morphology, syntax, phonography, etc.). Their corpora are then analyzed in terms of quantity, representativeness, and diversity of sources. A third section focuses on how they deal with variation (diachronic variation, diatopic variation, etc.), which is particularly significant during the Middle Ages. Finally, the role of theory is briefly mentioned. This overview highlights how grammars have supported and disseminated advances in research on the history of French and Medieval French. In a concluding section, some avenues for development are proposed, highlighting the diachronic and variationist perspectives that have been rapidly developing over the past few decades.