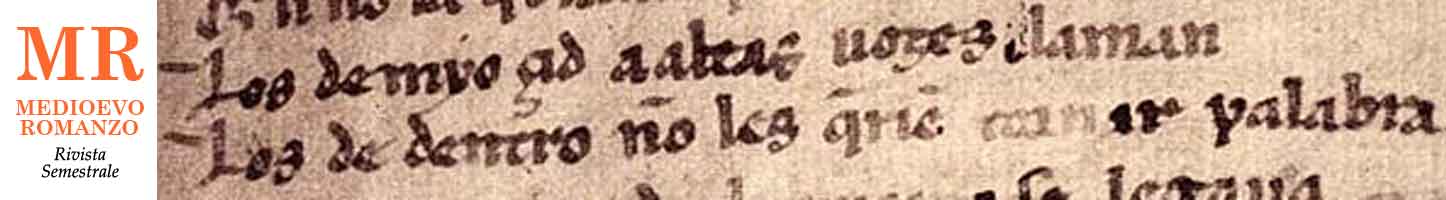

Il canzoniere BnF, Esp. 226, compilato a Napoli poco dopo il 1460, contiene la glosa de canción O dama desconocida per vari aspetti notevole: a differenza della maggior parte dei rappresentanti del genere, sviluppatosi tra XV e XVI secolo, il poeta altera l’ordine dei versi del testo base ma incorpora ciascun verso singolarmente, servendosi inoltre di coplas de pié quebrado di dodici versi. L’autore potrebbe forse identificarsi con il Furtado de Mendoza vissuto a Napoli durante il regno di Ferrante di Aragona (1458-1494).

The songbook BnF, Esp. 226, compiled in Naples shortly after 1460, contains the glosa de canción O dama desconocida in several respects notable: unlike most representatives of the genre, which developed between the 15th and 16th centuries, the poet alters the verse order of the basic text but incorporates each verse individually, making use of coplas de pié quebrado of twelve verses. The author could perhaps identify with Furtado de Mendoza who lived in Naples during the reign of Ferrante of Aragon (1458-1494).

L’aggettivo estrange usato nel Tristano Thomas per qualificare l’amore che unisce Marco, Isotta la bionda, Tristano e Isotta dalle bianche mani è stato variamente inteso dagli studiosi. Esso si riferisce in realtà allo squilibrio che lega un personaggio all’altro, per cui nessuno di loro può godere nella sua interezza dell’amato o amata, il che genera un senso di reciproca estraneità. La natura di questo “amore estraneo” è chiarita da un passaggio del De contemplando Deo di Guglielmo di Saint-Thierry, secondo cui l’infelicità umana deriva da un amore mal indirizzato, rivolto cioè alle cose mondane.

The adjective estrange used in Thomas’ Tristan to qualify the love that unites Mark, Isolde the Blonde, Tristan, and White-Handed Isolde has been variously understood by scholars. It actually refers to the imbalance that binds one character to the other, whereby neither of them can enjoy in his or her entirety the beloved, which generates a sense of mutual estrangement. The nature of this “estranged love” is clarified by a passage in William of Saint-Thierry’s De contemplando Deo, according to which human unhappiness results from misdirected love, that is, directed toward worldly things.

La tradizione del romanzo occitano Jaufre consiste di due mss. completi (Bnf, fr. 2164 e BnF, fr. 12571, entrambi della fine del XIII o dell’inizio del XIV secolo) e sei frammenti (quattro carte pergamenacee conservatesi in rilegature e due brani antologizzati in canzonieri lirici). I due manoscritti risalgono allo stesso capostipite i cui contorni sono ormai difficili da definire; i frammenti veri e propri sono più antichi dei due manoscritti e dei brani antologizzati. L’esame del rapporto testo-miniature e dell’uso di citazioni di Chrétien de Troyes può aiutare ad avvicinarsi all’originale, che sembra aver circolato, almeno in un primo tempo, tramite i giullari.

The tradition of the Occitan novel Jaufre consists of two complete ms. (Bnf, fr. 2164 and BnF, fr. 12571, both from the late 13th or early 14th century) and six fragments (four parchment papers preserved in bindings and two anthologized excerpts in lyric songbooks). The two ms. derive from the same model whose contours are now difficult to define; the actual fragments are older than the two ms. and the anthologized excerpts. The examination of the text-miniature relationship and of the use of quotations from Chrétien de Troyes may help to approximate the original, which seems to have circulated, at least at first, through jesters.